Vascular Tumors Treatment

Find comprehensive, compassionate care for pediatric vascular tumors affecting blood and lymph vessels at the Montefiore Einstein Comprehensive Cancer Center at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore Einstein (CHAM). CHAM provides state-of-the-art care for children from the New York metropolitan area, across the nation and around the world.

Cancer specialists at CHAM include nationally recognized physicians who offer a full range of treatments and clinical trials and exceptional support staff who are an integral part of our care team. This team includes dedicated oncology (cancer) nurses and nurse practitioners, social workers, registered dietitians, wellness staff, physical and occupational therapists, fertility preservation specialists (when appropriate) and child life specialists. Our collaborative approach to treatment ensures your child will receive the best care in a supportive and nurturing environment.

Our research efforts are designed to test promising new therapies, and clinical trials offer the most advanced, up-to-date treatment options.

When you want only the best for your child, turn to the caring specialists at Montefiore Einstein Comprehensive Cancer Center at CHAM, who are passionate about ending cancer and addressing your child’s whole health needs.

Cancer Clinical Trials

- Blood & Bone Marrow Cancers

- Brain, Spine & Central Nervous System Cancers

- Breast Cancer

- Childhood Cancers

- Endocrine System Cancers

- Gastrointestinal (GI) Cancers

- Genitourinary (GU) & Urologic Cancers

- Gynecologic Cancers

- Head & Neck Cancers

- Kaposi Sarcoma & AIDS-Related Cancers

- Lung & Chest Cancers

- Prostate Cancer

- Sarcomas

- Skin Cancer

As an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center, Montefiore Einstein Comprehensive Cancer Center supports the mission and guidelines of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The following information about types of cancer, prevention and treatments is provided by the NCI.

Childhood Vascular Tumors (PDQ®)–Patient Version

What are childhood vascular tumors?

Childhood vascular tumors are abnormal growths of blood vessels or lymph vessels that can occur anywhere in the body. These tumors may be benign (which means they are not cancer) or cancer. There are many types of vascular tumors. The most common type is infantile hemangioma, which is a benign tumor that usually goes away on its own.

Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors

In This Section

- Ultrasound exam

- CT scan (CAT scan)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Chest x-ray

- Biopsy

If your child has symptoms, such as discoloration on or under the skin, that suggest a vascular tumor, the doctor will need to find out if these are due to a vascular tumor or another problem. The doctor will ask when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They will also ask about your child's personal and family health history and do a physical exam. Depending on these results, they may recommend other tests. If your child is diagnosed with a vascular tumor, the results of these tests will help you and your child's doctor plan treatment.

The tests used to diagnose a vascular tumor in children may include:

Ultrasound exam

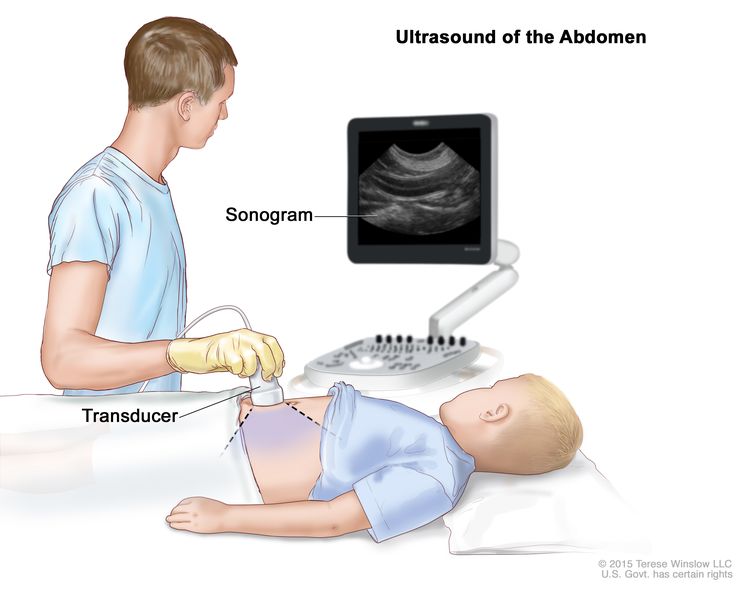

An ultrasound uses high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) that bounce off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram.

Abdominal ultrasound. An ultrasound transducer connected to a computer is pressed against the skin of the abdomen. The transducer bounces sound waves off internal organs and tissues to make echoes that form a sonogram (computer picture).

CT scan (CAT scan)

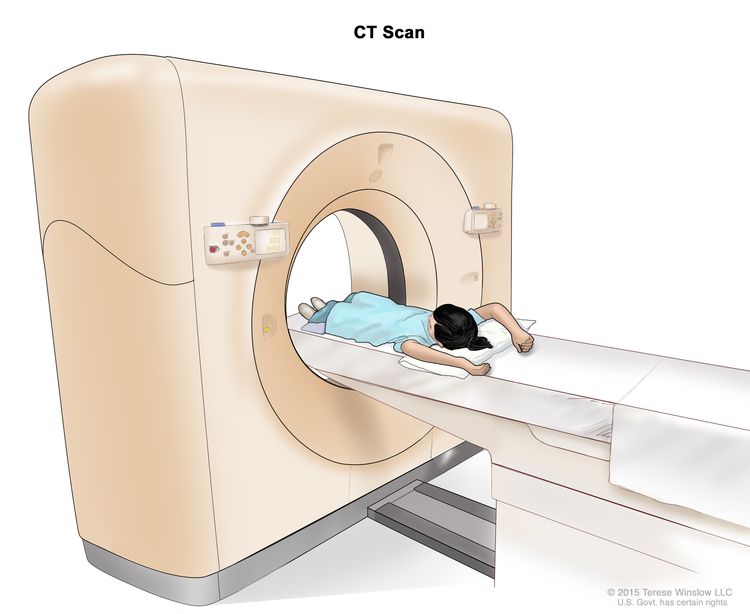

A CT scan uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The pictures are taken from different angles and are used to create 3-D views of tissues and organs. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography. Learn more about Computed Tomography (CT) Scans and Cancer.

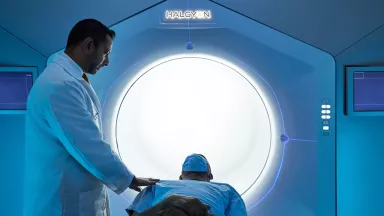

Computed tomography (CT) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the CT scanner, which takes a series of detailed x-ray pictures of areas inside the body.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

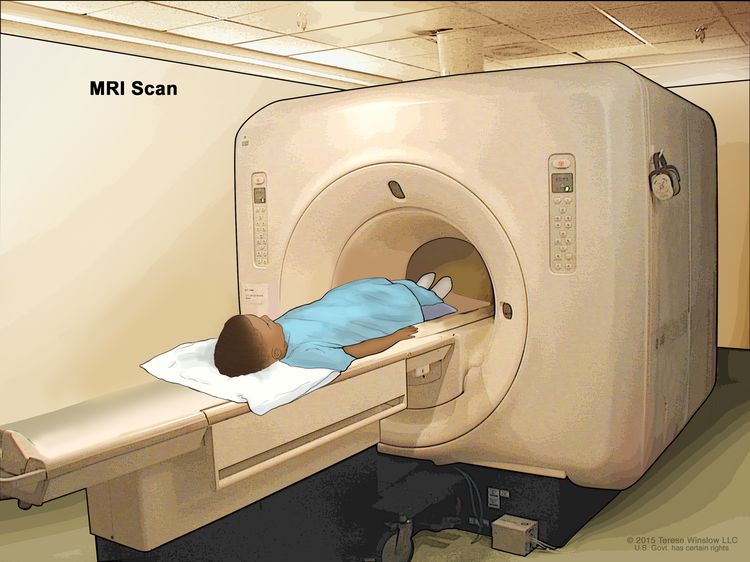

MRI uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

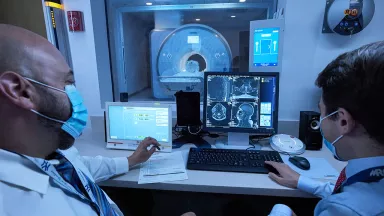

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The child lies on a table that slides into the MRI machine, which takes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The positioning of the child on the table depends on the part of the body being imaged.

Chest x-ray

An x-ray is a type of radiation that can go through the body and make pictures. A chest x-ray makes pictures of the organs and bones inside the chest.

Biopsy

Biopsy is a procedure in which a sample of tissue is removed from the tumor so that a pathologist can view it under a microscope to check for cancer. While a biopsy is not always needed to diagnose a vascular tumor, it may help find gene mutations that will help with treatment planning.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child's diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans. This doctor may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child's tumor.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, visit Finding Health Care Services. You can contact NCI's Cancer Information Service via chat, email, or phone (both in English and Spanish) for help finding a doctor or hospital that can provide a second opinion. For questions you might want to ask at your child's appointments, visit Questions to Ask Your Doctor.

Types of childhood vascular tumors

In This Section

- Benign tumors

- Infantile hemangioma

- Congenital hemangioma

- Benign vascular tumors of the liver

- Spindle cell hemangioma

- Epithelioid hemangioma

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Angiofibroma

- Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma

- Intermediate tumors that may spread locally

- Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma

- Intermediate tumors that may spread to other parts of the body

- Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma–like) hemangioendothelioma

- Retiform hemangioendothelioma

- Papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma

- Composite hemangioendothelioma

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Malignant tumors

- Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

- Angiosarcoma

Benign tumors

Benign vascular tumors are not cancer.

Infantile hemangioma

Infantile hemangioma (also called a strawberry mark) is the most common type of benign vascular tumor in children. It occurs when immature cells that are meant to form blood vessels form a tumor instead. It tends to appear between the ages of 3 to 6 weeks and is usually not seen at birth. The hemangioma often gets bigger for about 5 months and then stops growing. It slowly fades over the next several years, but a red mark or loose or wrinkled skin may remain. It is rare for an infantile hemangioma to come back after it has faded away.

Infantile hemangioma can develop anywhere on the body, including the skin, the tissue below the skin, or within an organ. It most commonly appears on the skin on the head and neck. Hemangioma may be a single lesion, one or more lesions spread over a larger area, or multiple lesions in different parts of the body. A hemangioma that covers a larger area, involves an organ, or has multiple lesions is more likely to cause problems.

- Hemangioma in the airway usually occurs along with a large hemangioma on the face that looks like a beard. Airway hemangioma may cause the airway to narrow, leading to trouble breathing.

- Periocular hemangioma involves the eye or tissues around the eye. It may cause vision problems or blindness and is sometimes linked with other eye problems.

- Having more than five hemangiomas on the skin is a sign that there may be hemangiomas in an organ, such as the liver, heart, muscle, or thyroid gland. The liver is affected most often.

Some hemangiomas appear between the ages of 3 to 6 weeks but do not grow bigger. This type of hemangioma is called infantile hemangioma with minimal or arrested growth. The lesion appears as light and dark areas of redness on the skin of the lower body or the head and neck. Hemangiomas of this type go away over time without treatment.

Causes and risk factors for infantile hemangioma

Infantile hemangioma is caused by certain changes to how the vascular cells function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. Often, the exact cause of these changes is unknown.

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. Not every child with a risk factor will develop an infantile hemangioma. And it can develop in some children who don't have a known risk factor.

Infantile hemangioma is more common in:

- girls

- White people

- premature babies

- twins, triplets, or other multiple births

- babies conceived using in vitro fertilization

- babies of mothers who are older at the time of the pregnancy, have pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure during pregnancy), or who have problems with the placenta during pregnancy

Other risk factors for infantile hemangioma include:

- Having a family history of infantile hemangioma, usually in a mother, father, or sibling.

- Having PHACE syndrome, a rare disorder marked by problems that affect the large blood vessels, heart, eyes, and/or brain. PHACE syndrome increases the risk of a hemangioma that spreads across a large area of the head or face and sometimes the neck, chest, or arm.

- Having LUMBAR/PELVIS/SACRAL syndrome, a rare disorder marked by problems that affect the urinary system, genitals, rectum, anus, brain, spinal cord, and nerve functions. This syndrome increases the risk of a hemangioma that spreads across a large area of the lower back, arms, chest, or legs.

Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

Symptoms of infantile hemangioma

Infantile hemangioma may cause any of the following symptoms. It's important to check with your child's doctor if your child has a:

- Lesion on the skin: An area of spidery veins or lightened or discolored skin may be the first sign of a hemangioma. This may develop into a firm, warm, bright red-to-crimson lesion on the skin that may look like a bruise. A lesion may also form an ulcer that is painful and can lead to bleeding, infection, and scarring. Later, as the hemangioma goes away, it becomes softer and begins fading in the center before flattening and losing color.

- Lesion below the skin: A lesion that grows under the skin in the fat may appear blue or purple. If the lesion is deep enough under the skin surface, it may not be seen.

- Lesion in an organ: There may be no symptoms if a hemangioma forms on an organ.

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than a hemangioma. The only way to know is for your child to see a doctor.

Diagnosis of infantile hemangioma

A physical exam and personal and family health history are usually all that are needed to diagnose infantile hemangioma. If the hemangioma looks unusual, a biopsy may be done. An ultrasound may be done if the hemangioma is deeper inside the body with no change to the skin or if the lesion covers a large area of the body. Infants with five or more hemangiomas on the skin should have an ultrasound of the liver to check for a liver hemangioma.

If the hemangioma is part of a syndrome, more tests, such as an echocardiogram, MRI, magnetic resonance angiogram, and eye exam, may be done.

Learn more about these tests in Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of infantile hemangioma

Most hemangiomas fade and shrink without treatment. If a hemangioma is large, causing other health problems, or in an area where it could cause serious problems if it grows bigger, treatment may include:

- beta-blocker therapy, such as propranolol, nadolol, or atenolol

- topical beta-blocker therapy for a hemangioma that is in one area of the skin

- steroid therapy, which may be used when beta-blocker therapy is being started or when beta-blockers cannot be used

- laser surgery, including pulsed dye laser surgery, which may be used for a hemangioma that has an ulcer or has not completely gone away

- surgery for a hemangioma that has an ulcer, causes vision problems, has not completely gone away, or is on the face and has not responded to other treatment

- combined therapy, such as propranolol and steroid therapy or propranolol and topical beta-blocker therapy

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Congenital hemangioma

Congenital hemangioma is a benign vascular tumor that begins forming before birth and is fully formed when the baby is born. It is usually on the skin but can be in another organ. A congenital hemangioma may occur as a rash of purple spots. The skin around the spot may be lighter.

There are three types of congenital hemangiomas. The differences between the three types relate to how they shrink (involute) over time:

- Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma (RICH) goes away on its own 12 to 15 months after birth. It can form an ulcer, bleed, and cause temporary heart and blood clotting problems. The skin may look a little different even after the hemangioma goes away.

- Partial involuting congenital hemangioma (PICH) may shrink on its own but does not go away completely.

- Non-involuting congenital hemangioma (NICH) stays the same size and never goes away on its own.

If your child has symptoms that suggest a congenital hemangioma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam and ultrasound exam to make the diagnosis.

The types of treatment your child may receive depend on whether the congenital hemangioma will shrink on its own.

- Treatment of rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma and partial involuting congenital hemangioma may be observation.

- Treatment of non-involuting congenital hemangioma may be surgery to remove the tumor, depending on where it is and whether it is causing symptoms.

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Benign vascular tumors of the liver

Benign vascular tumors of the liver may be:

- a single lesion in one part of the liver (focal vascular lesion)

- several lesions in one part of the liver (multiple liver lesions)

- several lesions spread across different parts of the liver (diffuse liver lesions)

The liver has many functions, including filtering blood and making proteins that help with blood clotting. Sometimes, the tumor can block or slow the normal flow of blood through the liver. When this happens, blood is sent directly to the heart without going through the liver. This condition is known as a liver shunt. It can cause heart failure and problems with blood clotting.

If your child has symptoms that suggest a benign vascular tumor of the liver, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam and ultrasound exam to make the diagnosis.

The treatment your child may receive depends on whether they have a focal vascular lesion, multiple liver lesions, or diffuse liver lesions.

A single lesion in one part of the liver (focal vascular lesion) is usually a rapidly involuting (shrinking) congenital hemangioma or a non-involuting congenital hemangioma. This lesion can be diagnosed before birth or shortly after the baby is born. Treatment of this type of lesion depends on whether symptoms occur and may include:

- observation

- embolization of the liver to treat symptoms

- surgery, for lesions that do not respond to other treatments

Multiple and diffuse liver lesions are usually infantile hemangiomas. Diffuse liver lesions can cause serious effects, including problems with thyroid hormones and the heart. The liver can enlarge, press on other organs, and cause more symptoms.

Treatment of multiple liver lesions may include:

- observation for lesions that do not cause symptoms

- beta-blocker therapy (propranolol) for lesions that begin to grow

Treatment of diffuse liver lesions may include:

- beta-blocker therapy (propranolol)

- chemotherapy

- steroid therapy

- total hepatectomy and liver transplant, for lesions that do not respond to drug therapy or for diffuse liver lesions that are spreading and causing organ failure and there is no time to start treatment

Children with diffuse liver lesions may be diagnosed with hypothyroidism caused by the liver tumor using more of the thyroid hormone. These children may need thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

If a vascular liver lesion does not respond to treatment, a biopsy may be done to see if the tumor is cancer.

Spindle cell hemangioma

A spindle cell hemangioma contains cells called spindle cells. Under a microscope, spindle cells look long and slender. A spindle cell hemangioma is a painful red-brown or bluish lesion that usually appears on the arms or legs. It can begin as one lesion and develop into more lesions over the years. A spindle cell hemangioma can form in children and adults.

Some children may be at increased risk of developing a spindle cell hemangioma. A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. Not every child with a risk factor will develop a spindle cell hemangioma. And it can develop in some children who don't have a known risk factor. Spindle cell hemangiomas are more likely to develop in children with the following syndromes:

- Maffucci syndrome, which affects cartilage and skin

- Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, which affects blood vessels, soft tissues, and bones

Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

If your child has symptoms that suggest a spindle cell hemangioma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. If needed, tests may be done. Learn more about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Although there is no standard treatment for spindle cell hemangioma, surgery may be used to remove the tumor. Spindle cell hemangioma may come back after surgery.

Epithelioid hemangioma

An epithelioid hemangioma most often forms on or in the skin, especially the head, but can occur in other areas, such as bone. An epithelioid hemangioma is sometimes caused by injury. It occurs in children and adults.

On the skin, an epithelioid hemangioma may appear as firm pink-to-red bumps and may be itchy. Epithelioid hemangioma of the bone may cause swelling, pain, and weakened bone in the affected area or symptoms of nerve injury. These symptoms may be caused by problems other than an epithelioid hemangioma. The only way to know is for your child to see a doctor.

If your child has symptoms that suggest an epithelioid hemangioma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. An MRI, x-ray, or biopsy may also be done. Learn more about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

There is no standard treatment for epithelioid hemangioma. Treatment may include:

- surgery (curettage or resection)

- sclerotherapy

- radiation therapy in rare cases

Epithelioid hemangioma often comes back after treatment.

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Pyogenic granuloma

Pyogenic granuloma is also called lobular capillary hemangioma. It is most common in older children and young adults but can occur at any age.

Pyogenic granuloma is sometimes caused by injury or from the use of certain medicines, including birth control pills and retinoids. It may also form for no known reason inside capillaries (the smallest blood vessels), arteries, veins, or other places on the body. Some lesions may be associated with capillary malformations.

Pyogenic granuloma is a raised, bright red lesion that may be small or large and smooth or bumpy. It grows quickly over weeks to months and may bleed a lot. The lesion is on the skin's surface but may form in the tissues below the skin and look like other vascular lesions. Usually, there is only one lesion. Sometimes multiple lesions can occur in the same area or on different parts of the body. The only way to know if these symptoms are caused by a pyogenic granuloma is for your child to see a doctor.

If your child has symptoms that suggest a pyogenic granuloma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. If needed, tests may be ordered. Learn more about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Pyogenic granuloma can go away without treatment. Sometimes a pyogenic granuloma needs treatment that may include:

- surgery (excision or curettage) to remove the lesion

- photocoagulation

- cryotherapy

- topical beta-blocker therapy (propranolol or timolol)

Pyogenic granuloma often comes back after treatment.

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Angiofibroma

Angiofibroma is rare and appears as red bumps on the face. It is a benign skin lesion that usually occurs with tuberous sclerosis, an inherited disorder that causes skin lesions, seizures, and mental disabilities. Talk to your child's doctor if you think your child may have an angiofibroma.

If your child has symptoms that suggest an angiofibroma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. If needed, tests may be ordered. Learn more about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of angiofibroma may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor

- laser therapy

- targeted therapy (sirolimus)

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is a tumor that is not cancer but can grow into nearby tissues. It is most common in males and may form around the time of puberty. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma begins in the nasal cavity and may spread to the nasopharynx, the paranasal sinuses, the bone around the eyes, and sometimes to the brain.

If your child has symptoms that suggest juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. If needed, tests may be ordered. Learn more about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor

- radiation therapy

- chemotherapy

- immunotherapy (interferon)

- targeted therapy (sirolimus)

This tumor may come back after treatment.

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Intermediate tumors that may spread locally

Some intermediate tumors are likely to spread to the area around the tumor (locally), but not to other parts of the body.

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma are blood vessel tumors that occur in infants or young children and affect males and females equally. These tumors can cause Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon, a condition in which the blood is not able to clot and serious bleeding may occur. This type of vascular tumor is not related to Kaposi sarcoma.

Symptoms of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma usually occur on the skin of the arms and legs, but may also form in deeper tissues, such as muscle or bone, or in the chest, abdomen, head, or neck.

Symptoms may include:

- firm, warm, painful areas of skin that look bruised

- purple or brownish-red areas of skin

- pain with no visible lump

- easy bruising

- bleeding more than the usual amount from mucous membranes, wounds, and other tissues

People who have kaposiform hemangioendothelioma or tufted angioma may have anemia (weakness, feeling tired, or looking pale).

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than kaposiform hemangioendothelioma or tufted angioma. The only way to know is for your child to see a doctor.

Diagnosis of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma

If a physical exam and MRI clearly show the tumor is a kaposiform hemangioendothelioma or a tufted angioma, a biopsy may not be needed. A biopsy is not always done because serious bleeding can occur. An ultrasound exam may also be used to diagnose a tufted angioma.

Learn more about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma are best treated by a vascular anomaly specialist. Treatment depends on the symptoms, size and location of the tumor, and the risk of bleeding. Infection, delay in treatment, and surgery can cause bleeding that is life-threatening.

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma may be called uncomplicated or complicated.

Uncomplicated tumors are in one area, smaller, cause few or no symptoms, and have a lower risk of bleeding. People with an uncomplicated tumor do not have Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon.

Treatment for uncomplicated kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma may include:

- observation for tumors with a low risk of getting worse

- surgery to remove the tumor

- laser surgery

- topical therapy (steroids or tacrolimus)

- beta-blocker therapy (propranolol)

- targeted therapy (sirolimus) with or without steroid therapy

Complicated tumors are larger, may cause symptoms, and affect how the body functions. People with a complicated tumor may have Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon, a serious condition that can be life-threatening and requires treatment.

Treatment for complicated kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma may include:

- chemotherapy, with or without steroid therapy

- targeted therapy (sirolimus), with or without steroid therapy

- surgery, with or without embolization

Even with treatment, these tumors do not fully go away and can come back. Pain and inflammation may get worse with age, often around puberty. Long-term effects include chronic pain, heart failure, bone problems, and lymphedema (the build up of lymph fluid in tissues).

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Intermediate tumors that may spread to other parts of the body

Rarely, intermediate tumors spread to other parts of the body (metastasize).

Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma–like) hemangioendothelioma

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma can occur in children, but is most common in men aged 20 to 50 years. This tumor is rare, and usually occurs on or under the skin or in bone. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma may appear as a lump in soft tissue or may cause pain in the affected area. It may spread to nearby tissue but usually does not spread to other parts of the body. In most cases, there are multiple tumors. Talk to your child's doctor if you think your child may have pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma.

If your child has symptoms that suggest pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. If needed, tests may be ordered. Learn about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor when possible or amputation may be needed when there are multiple tumors in the bone

- chemotherapy

- targeted therapy (pazopanib)

Because pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is so rare in children, treatment options are based on clinical trials in adults.

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Retiform hemangioendothelioma

Retiform hemangioendothelioma is a slow-growing, flat tumor that occurs in young adults and sometimes children. This tumor usually occurs on or under the skin of the arms, legs, and trunk. It usually does not spread to other parts of the body. Talk to your child's doctor if you think your child may have a retiform hemangioendothelioma.

If your child has symptoms that suggest retiform hemangioendothelioma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. If needed, tests may be ordered. Learn about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of retiform hemangioendothelioma may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor

- radiation therapy and chemotherapy when surgery cannot be done or when the tumor has come back

Retiform hemangioendothelioma may come back after treatment.

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma

Papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma is also called Dabska tumor. It occurs in children and adults.

Papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma may appear as firm, raised, purplish bumps, which may be small or large. Papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma forms in or under the skin anywhere on the body. Sometimes the lymph nodes are affected. Talk to your child's doctor if you think your child may have papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma.

If your child has symptoms that suggest papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. If needed, tests may be ordered. Learn about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma is surgery.

Learn more about this treatment in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Composite hemangioendothelioma

Composite hemangioendothelioma has features of both benign and malignant vascular tumors. This tumor usually occurs on or under the skin of the arms or legs. It may also occur on the skin of the head, neck, or chest. Composite hemangioendothelioma is not likely to spread to nearby tissue or to other parts of the body, but it may come back in the same place. If the tumor spreads, it usually spreads to nearby lymph nodes. Composite hemangioendothelioma occurs in children and adults.

If your child has symptoms that suggest composite hemangioendothelioma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. If needed, tests may be ordered. Learn about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of composite hemangioendothelioma may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor

- radiation therapy and chemotherapy for tumors that have spread

Composite hemangioendothelioma may come back after treatment.

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Kaposi sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma is a cancer that causes lesions to grow in the skin; the mucous membranes lining the mouth, nose, and throat; lymph nodes; or other organs. It is caused by human herpesvirus 8. This cancer rarely occurs in children. In the United States, Kaposi sarcoma occurs most often in children who have a weak immune system caused by rare immune system disorders, HIV infection, or drugs used in organ transplants. In sub-Saharan Africa, Kaposi sarcoma is endemic and often occurs in children and young adults.

Kaposi sarcoma are lesions that form in the skin, mouth, or throat. The lesions are red, purple, or brown and change from flat, to raised, to scaly areas called plaques, to nodules. Sometimes Kaposi sarcoma causes swollen lymph nodes. These symptoms may be caused by problems other than Kaposi sarcoma. The only way to know is to see your child's doctor.

If your child has symptoms that suggest Kaposi sarcoma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. If needed, tests may be ordered. Learn about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of Kaposi sarcoma may include:

Learn more about these treatments in the Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Because Kaposi sarcoma is so rare in children, some treatment options are based on clinical trials in adults. Learn more at Kaposi Sarcoma Treatment.

Malignant tumors

Malignant tumors are cancer.

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma can occur in children, but is most common in adults aged 30 to 50 years. It may occur in the liver, lung, bone, skin, or soft tissue. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma may be fast growing or slow growing. In about a third of patients with a tumor in the soft tissue, the tumor spreads to other parts of the body very quickly.

Symptoms of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

The symptoms of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma depend on where the tumor is in the body. It's important to check with your child's doctor if your child has:

- red-brown patches on the skin that are raised and rounded or flat and feel warm

- early symptoms of lesions in the lung, which may not occur in all children with lung lesions:

- chest pain

- spitting up blood

- anemia (weakness, feeling tired, or looking pale)

- trouble breathing (from scarred lung tissue)

- broken bones

- symptoms of lesions in the liver:

- itching

- yellowing of the skin or eye

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than an epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. The only way to know is for your child to see a doctor.

Diagnosis of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

If your child has symptoms that suggest epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam to make the diagnosis. The doctor may also order tests. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma in the liver is found with an ultrasound exam, CT scan or MRI scan. X-rays of the chest or other areas of the body may also be done. Learn more about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

Treatment of slow-growing epithelioid hemangioendothelioma may be observation. Surgery may be used when it is possible to remove the tumor.

Treatment of fast-growing epithelioid hemangioendothelioma may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor when possible

- immunotherapy (interferon) for tumors that are likely to spread

- targeted therapy (pazopanib or sirolimus) for tumors that are likely to spread

- chemotherapy

- radiation therapy

- palliative care

Learn more about these treatments in the Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Angiosarcoma

Angiosarcoma is a fast-growing tumor that forms in blood vessels or lymph vessels in any part of the body, usually in the soft tissue. Most angiosarcoma is in the skin or in the soft tissue near the skin. Those in deeper soft tissue can form in the liver, spleen, and lung.

Angiosarcoma is very rare in children. Children sometimes have more than one tumor in the skin, liver, or both.

Causes and risk factors for angiosarcoma

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. Not every child with a risk factor will develop angiosarcoma. And it can develop in some children who don't have a known risk factor. Risk factors for angiosarcoma include:

- being exposed to radiation

- chronic (long-term) lymphedema, a condition in which extra lymph fluid builds up in tissues and causes swelling

- having a benign vascular tumor

Rarely, a benign vascular tumor, such as a hemangioma, may become an angiosarcoma.

Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

Symptoms of angiosarcoma

Symptoms of angiosarcoma depend on where the tumor is and may include:

- red patches on the skin that bleed easily

- purple tumors

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than an angiosarcoma. The only way to know is for your child to see a doctor.

Diagnosis of angiosarcoma

To make a diagnosis, the doctor will ask about your child's personal health history and do a physical exam. If needed, tests may be ordered. Learn about Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Treatment of angiosarcoma

Treatment of angiosarcoma may include:

- surgery to completely remove the tumor

- a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy for angiosarcoma that has spread

- palliative care

Learn more about these treatments in Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors.

Types of treatment for childhood vascular tumors

In This Section

- Who treats children with vascular tumors?

- Treatment options

- Beta-blocker therapy

- Surgery

- Photocoagulation

- Cryotherapy

- Embolization

- Chemotherapy

- Sclerotherapy

- Radiation therapy

- Targeted therapy

- Immunotherapy

- Other drug therapy

- Observation

- Clinical trials

Who treats children with vascular tumors?

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, oversees treatment for childhood vascular tumors. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with cancer and also specialize in certain areas of medicine. Other specialists may include:

- pediatric vascular anomaly specialist (expert in treating children with vascular tumors)

- pediatric surgeon

- pediatric dermatologist

- pediatric hematologist and oncologist

- orthopedic surgeon

- radiation oncologist

- pediatric nurse specialist

- rehabilitation specialist

- psychologist

- social worker

Treatment options

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with vascular tumors. You and your child's care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as where the tumor is located, your child's age and overall health, the type of vascular tumor, the risk of scarring, and the likelihood of completely treating the vascular tumor.

Your child's treatment plan will include information about the tumor, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child's care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, see our booklet, Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Types of treatment your child might have include:

Beta-blocker therapy

Beta-blockers are drugs commonly used to lower blood pressure and heart rate, but they can also shrink certain types of vascular tumors, such as infantile hemangiomas. Beta-blocker therapy may be injected into a vein, taken by mouth, or placed on the skin (topical). How beta-blocker therapy is given depends on the type of vascular tumor being treated and where it first formed.

The beta-blocker propranolol is usually the first treatment for hemangiomas. Infants younger than 4 weeks, who have an underlying condition, or who are treated with IV propranolol may need to have their treatment started in a hospital. Infantile hemangioma may also be treated with propranolol and steroid therapy or propranolol and topical beta-blocker therapy. Propranolol is also used to treat benign vascular tumors of liver.

Other beta-blockers used to treat vascular tumors include atenolol, nadolol, and timolol.

Surgery

The following types of surgery may be used to remove many types of vascular tumors:

- Excision is surgery to remove the entire tumor and some of the healthy tissue around it.

- Laser surgery uses a laser beam (a narrow beam of intense light) as a knife to make bloodless cuts in tissue or remove a skin lesion such as a tumor. Surgery with a pulsed dye laser may be used for some hemangiomas. This type of laser uses a beam of light that targets blood vessels in the skin. The light is changed into heat and the blood vessels are destroyed without damaging nearby skin.

- Curettage uses a small, spoon-shaped instrument with a sharp edge called a curette to remove abnormal tissue.

- Total hepatectomy and liver transplant removes the entire liver followed by a transplant of a healthy liver from a donor.

- Amputation removes an arm or leg when there are multiple tumors in the bone.

The type of surgery used depends on the type of vascular tumor and where it formed in the body.

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, some people may be given chemotherapy or radiation therapy to kill any cancer cells that are left. Treatment given after the surgery to lower the risk that the cancer will come back is called adjuvant therapy.

Photocoagulation

Photocoagulation is the use of an intense beam of light, such as a laser, to seal off blood vessels or destroy tissue. It is used to treat pyogenic granuloma.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy uses an instrument to freeze and destroy abnormal tissue, such as abnormal blood vessels in pyogenic granuloma. This type of treatment is also called cryosurgery.

Learn more about Cryosurgery to Treat Cancer.

Embolization

Embolization uses particles, such as tiny gelatin sponges or beads, to block blood vessels in the liver. It may be used to block blood flow to some benign vascular tumors of the liver and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of tumor cells. Chemotherapy either kills the cancer cells or stops them from dividing. Chemotherapy may be given alone or with other types of treatment.

For some vascular tumors, chemotherapy is injected into a vein. When given this way, the drugs enter the bloodstream to reach tumor cells throughout the body.

Chemotherapy drugs that may be used alone or in combination to treat childhood vascular tumors include:

Other chemotherapy drugs not listed here may also be used.

Learn more about how chemotherapy works, how it is given, common side effects, and more at Chemotherapy to Treat Cancer.

Sclerotherapy

Sclerotherapy destroys the tumor and the blood vessels that lead to it. A liquid is injected into the blood vessels, causing them to scar and break down. Over time, the destroyed blood vessels are absorbed into normal tissue. The blood flows through nearby healthy veins instead. Sclerotherapy is used to treat epithelioid hemangioma.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill tumor cells or keep them from growing. External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with the tumor. It is used to treat some vascular tumors.

Learn more about External Beam Radiation Therapy for Cancer and Radiation Therapy Side Effects.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy uses drugs or other substances to block the action of specific enzymes, proteins, or other molecules involved in the growth and spread of cancer cells. Different types of targeted therapy are being used or studied to treat childhood vascular tumors:

Learn more about Targeted Therapy to Treat Cancer.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy helps a person's immune system fight cancer. Interferon is a type of immunotherapy used to treat vascular tumors.

Learn more about Immunotherapy to Treat Cancer.

Other drug therapy

Other drugs used to treat childhood vascular tumors or manage their effects include:

- Steroid therapy: Steroids are hormones made naturally in the body. They can also be made in a laboratory and used as drugs. Steroid drugs help shrink some vascular tumors. Corticosteroids, such as prednisone and methylprednisolone, are used to treat infantile hemangioma.

- Immunosuppressant therapy: These drugs decrease the body's immune responses. Immunosuppressant therapy has been used to help shrink vascular tumors. Topical tacrolimus is used to treat kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas and tufted angiomas.

- Thyroid hormone replacement therapy: These drugs replace hormones made by the thyroid and are used to treat a rare form of hypothyroidism caused by some vascular tumors, such as liver hemangiomas.

Observation

Observation is closely monitoring a person's condition without giving any treatment until symptoms appear or change.

Clinical trials

For some children, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for childhood cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials accepting participants. The search allows you to filter trials based on the type of cancer, your child's age, and where the trials are being done. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Side effects and late effects of treatment

Treatments for vascular tumors can cause side effects. Which side effects your child might have depends on the type of treatment they receive, the dose, and how their body reacts. Talk with your child's treatment team about which side effects to look for and ways to manage them.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit Side Effects.

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of treatment may include:

- physical problems

- changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory

- second cancers (new types of cancer)

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the possible late effects caused by some treatments. Learn more about Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer.

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the vascular tumor may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the tumor has come back.

Learn more about follow-up tests in Tests to diagnose childhood vascular tumors.

Coping with your child's vascular tumor

When your child has a tumor, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is important. Reach out to your child's treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, visit Support for Families: Childhood Cancer and the booklet Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Related resources

For more childhood cancer information and other general cancer resources, visit:

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government’s center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood vascular tumors. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Vascular Tumors. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma/patient/child-vascular-tumors-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 27253005]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s E-mail Us.

Updated:

Source URL: https://www.cancer.gov/node/1050998/syndication

Source Agency: National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Captured Date: 2016-06-03 07:39:47.0