Feature

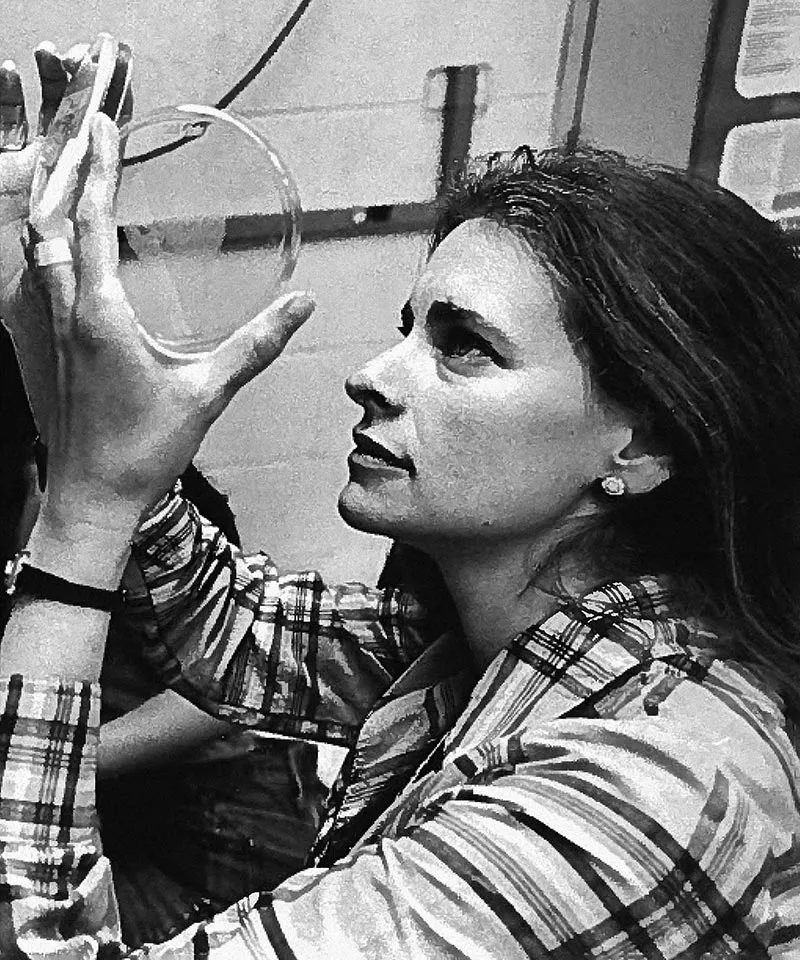

Dr. Lucy Shapiro: Celebrating A Scientific Life

Renowned molecular and developmental biologist Lucy Shapiro, Ph.D. ’66, is still making groundbreaking discoveries

September 17, 2025

Editor’s Note: Einstein alumna Lucy Shapiro, Ph.D. ’66, was awarded the 2025 Lasker-Koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science. This interview with Dr. Shapiro originally ran in the summer/fall 2023 issue of Einstein magazine. All photos are courtesy of Dr. Shapiro.

For Dr. Lucy Shapiro, director of the Beckman Center for Molecular and Genetic Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine, life has been a series of defining moments, all rooted in science. From the moment in college when she first saw a three-dimensional image of an organic molecule, she was hooked. “I have a photographic memory, and I can rotate things in space in my head,” she explains, “and I realized that organic chemistry is just beautiful.”

Dr. Shapiro received her doctorate in molecular biology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and became its first female chair of a department in 1977. She would later launch the field of systems biology at Stanford, advise two U.S. presidents on antibiotic resistance and bioterrorism threats, receive the National Medal of Science from President Barack Obama, and co-found biotech companies, among many other accomplishments. She attributes much of her success to the training she received at Einstein, which was “extraordinary, demanding, and rigorous, but always supportive.”

We caught up with Dr. Shapiro, who recently celebrated her 83rd birthday, to ask her about those defining moments and how they shaped her remarkable career.

You went to the High School of Music and Art in Harlem to become a painter but ended up double majoring in fine arts and biology in college. Why biology?

When I entered Brooklyn College, it had just started its honors program. Ten of us entering freshmen were chosen for the program, which meant that we didn’t have any requirements. I did what I wanted, mostly art, and helped support myself in college by doing medical illustration. Biology was interesting and DNA was hot—it was the beginning of molecular biology, understanding the biochemical underpinnings of this new world that had started in 1953 with [James] Watson and [Francis] Crick’s discovery of the double helix. So I also took biology courses but never stopped the art.

How did you end up at Einstein?

While I was still at Brooklyn College, I had a painting on exhibit at an art show and met a scientist, Theodore Shedlovsky [Ph.D.], who was there from Rockefeller University. He was a distinguished physical chemist and a violinist and would find young people in the arts who had potential and convince them to give science a chance. He urged me to take organic chemistry. I had no chemistry background but managed to enroll in Brooklyn College’s honors organic chemistry course and got an A. That course was the beginning of the rest of my life—one of my defining moments.

After I graduated, Dr. Shedlovsky encouraged me to get some experience in a lab. He sent me to Jerry Hurwitz and Tom August’s lab in the department of microbiology at the New York University School of Medicine. They were studying DNA-dependent RNA polymerases. I knew how to make up a molar solution and so they hired me. It was a tough, male-oriented lab, and a lot was expected of us. This was the heyday of molecular biology discoveries, and we were a fulcrum with people coming from all over the world to visit the lab, so when I was offered the opportunity to pursue a Ph.D., I agreed.

The following year, the entire department moved to the Bronx and its new home at Einstein, reconstituted as the department of molecular biology. The training I got at Einstein was demanding and rigorous; there was no question that we were taught to be the best in the world. At that point in the evolution of molecular biology, we knew only about copying DNA to make RNA. Reverse transcription from RNA to DNA came much later. But in the mid-1960s, for my Ph.D. research at Einstein, I had studied the first RNA-containing phage [bacterial virus] to be identified. And I discovered that, in order to multiply, it used an RNA replicase—an enzyme that catalyzes RNA replication from an RNA template. In 2020, the SARS-CoV-2 virus RNA replicase was the prime villain in the COVID-19 pandemic that swept the world.

After you’d spent six months in the lab of Julius Marmur, Ph.D., as a postdoctoral fellow, Einstein’s chair of molecular biology, Bernard Horecker, Ph.D., asked you to return as a faculty member. He told you that you could work on whatever you liked.

Yes, that was another defining moment. He said to me, “I want you to start a lab, but not for three months. First I want you to think and read and decide what important question is out there that you would want to explore.” Can you imagine a greater gift to a young scientist? That was unbelievable. So I came up with the idea of using the bacterium Caulobacter [crescentus] to address a key unanswered question in molecular biology.

What was that?

All cells exist in three dimensions, but where is the genetic code that tells them where to put things? Development and differentiation critically depend on asymmetric cell divisions that give you two different daughter cells. We didn’t have a clue how that happens. So I decided to find the simplest system I could study. That was Caulobacter crescentus, a bacterium that yields two different cells with each division: a swimming cell with a flagellum and a nonmotile cell with a stalk to keep it in place.

And so began my work on Caulobacter, for which I’ve won many prizes, including my capstone award, the 2022 Linus Pauling Gold Medal from Stanford University.

You were chair of departments at Einstein and then Columbia. How did you end up across the country at Stanford?

I had been at Columbia for only three years when Stanford asked me to start a new department there. I kept saying no. But one day one of the most famous scientists at Stanford appeared at my office at Columbia, unannounced, with a dozen yellow roses. I went home and told my husband, Harley McAdams [Ph.D.], a physicist and a department head at Bell Labs at the time. And he looked at me and said, “How often does anyone get a job offer like you’ve just gotten, to build a new department of developmental biology with a check for $12 million to hire faculty? And how often does a woman get an offer like that? We’re going.” Not only did he become a Stanford professor of developmental biology, but we ended up integrating our separate labs.

How did that work?

Harley’s students were physicists and engineers; my students were biochemists, bacteriologists, geneticists, and cell biologists. And we each had our group of students and postdocs, but we then put them together. So a physicist would sit at the bench next to a geneticist, and an engineer would sit at a desk next to a cell biologist. It was really the beginning of interdisciplinary work at Stanford. And more and more labs started doing that. It was just a cauldron of discovery. We had group meetings every week. If one of my biochemists was giving a talk, an engineer had to understand what we were talking about. So we were teaching each other each other’s language. And the work that resulted was transformational. More and more labs at Stanford began doing that. I really believe that the constant breakthroughs that came out of that lab were because of the interdisciplinary nature of what we did.

You’ve been a mentor to countless students at Stanford; 40 of your mentees are now leading Caulobacter labs of their own. Why is mentoring so important?

Every time they have a success, it’s my success. And every time they do something that’s exciting, I can build on it. That’s what science is like. When someone learns something, you say, “Oh, well, what can I do with that? What did that tell me that I didn’t know before? What experiments can I do to expand upon that?”

How did you come to serve as a scientific adviser to the White House?

In the early 1990s, I became very worried about the threats to the public posed by the increase in antibiotic resistance, emerging infectious diseases, and the possibility of bioterrorism. By then I was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, with a bully pulpit. I wanted to tell the people in power in Washington about my concerns—and did. I was invited to the White House to speak to President Bill Clinton and his Cabinet about antibiotic resistance. That led to serving as a scientific adviser to President Clinton and, during George W. Bush’s presidency, as an adviser on bioterrorism to the secretary of homeland security, Tom Ridge, and to the secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice.

You and Stephen Benkovic, Ph.D., a chemist at Pen State, decided to design antibiotics and antifungals based on boron as their active site rather than carbon. Why boron?

We looked at the periodic table, and there was boron right below carbon. Steve is a visionary chemist, and it was curiosity that drove him to build new molecules as potential drugs. That’s what science is all about. We were told, “Those compounds will be toxic—don’t waste your time.” But we tried it. Steve built a whole series of molecules centered on boron. He sent the compounds to me for testing, and several had incredible activity against specific bacterial and fungal pathogens.When we replaced the boron in those compounds with carbon, we found that they lost all activity—proof that boron was key to their success as potential drugs. Stanford and Penn State, where Steve is a professor of chemistry, patented our compounds. Then Steve and I pulled whatever resources we had and obtained the exclusive license to these patents to form the company Anacor Pharmaceuticals, focused on anti-infectives based on boron chemistry.

What’s your next venture?

After selling Anacor to Pfizer, I turned my attention to the crop losses in developing countries due to fungal infections, one of the consequences of climate change. So in 2017, Steve and I formed the company Boragen with the goal of discovering boron-centered compounds to prevent fungal-caused crop blights. In 2021 Boragen became 5Metis, and one of our compounds, for eliminating a fungus that devastates bananas, is being evaluated in the equivalent of phase 3 trials in Nigeria, Uganda, and Brazil, and it appears highly promising. These compounds are also effective against other fungal diseases, including wheat rust, soybean blight, and the fungus that kills sorghum, a nutritious cereal grain that feeds half the world.

Anything else you’d like to tell us about pursuing a career in science?

Be confident. Be brave. And if you don’t feel confident, act confident.