Feature

From the Bayou to the Bronx: Hooked on Discovery Q&A with Alexander Ledet, MSTP Student

July 22, 2025

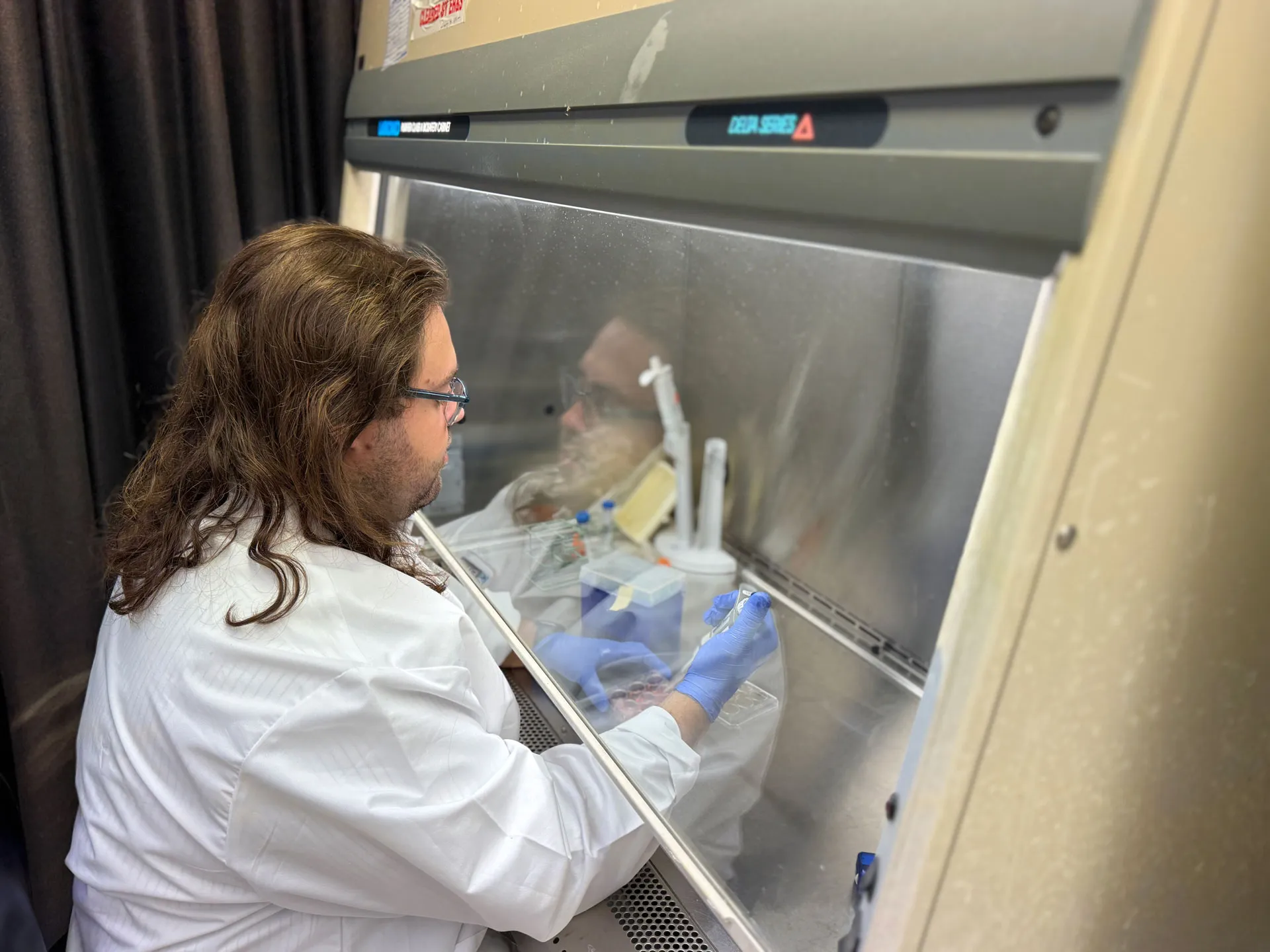

Alexander Ledet in the lab of Dr. Esperanza Arias-Perez

Alexander Ledet, a sixth-year MD-PhD student in the Medical Scientist Training Program at Montefiore Einstein, recently won Best Poster at the 2024 Pathology Research Retreat for his work on chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) – a crucial cellular quality-control system that breaks down in fatty liver disease. In the labs of Esperanza Arias-Perez, PhD, associate professor of medicine (hepatology) and pathology, and Ana Maria Cuervo, MD, PhD, distinguished professor of developmental & molecular biology, and medicine (hepatology), Ledet is investigating therapies that restore CMA and could improve liver health.

A Louisiana native, Ledet grew up fishing on the bayou. As a Tulane undergrad, he joined an ecology lab studying fish in the Gulf of Mexico. A discovery about altered fish reproduction tied to fertilizer runoff sparked his fascination with how cellular systems respond to stress, setting him on a path toward becoming a physician-scientist.

“What stands out about Alex is his deep curiosity and rigorous scientific mindset and his exceptional ability to connect complex molecular mechanisms to pressing clinical questions,” said Dr. Esperanza Arias-Perez, whose research focuses on proteostasis, aging, metabolic liver diseases, and liver cancer. She notes that his experimental work at the bench is equally impressive—methodical, innovative, and consistently high-quality—reflecting both his dedication and technical expertise. And Ledet’s talent for clearly explaining complex ideas hasn’t gone unnoticed. “He is a gifted communicator who can clearly convey intricate scientific ideas to diverse audiences,” Dr. Arias-Perez added.

In this Q&A with The Scope, Ledet shares how his journey—from fishing to researching liver disease in the lab—has been shaped by curiosity, mentorship, and a strong sense of place. He talks about the unexpected discovery in the Gulf that sparked his passion for research, the mentors who guided him, and the ways music and nature help him stay grounded.

Early Inspiration & The Fish That Changed Everything

Q: Where did you grow up and what first sparked your interest in science and medicine?

I grew up in Chauvin, Louisiana in a house on the bayou. It’s a one stoplight town an hour and a half south of New Orleans, about 20 minutes away from the end of the road and the start of the Gulf of Mexico. My interest in medicine developed slowly as I grew up and started to explore career options. Several of my family members have been impacted by chronic illnesses, and I think my initial interest in medicine was sparked due to a desire to alleviate that burden in an impactful way. Towards the end of high school, I started shadowing local doctors and picked a degree path that would allow me to become a physician during my undergraduate studies.

Q: You started your research career with a project that feels very rooted in your background. Can you tell us about that?

I hadn’t been exposed to research before going to college at Tulane, and surprisingly, my first research experience resulted from a required Ecology class. During the laboratory associated with that class, Mike, the PhD student TA for my laboratory section, shared what his thesis project was investigating. I became quite interested, as his project was essentially centered around the impacts of low oxygen levels on small fish in the Gulf of Mexico that I had used as bait growing up. I knew that undergraduate research experience enhances medical school applications; because of that and my personal connections to Mike’s work, I asked his PI to join the lab and the project. Although I was unaware at the time, that chance placement into Mike’s laboratory section altered my career aspirations.

During the two years I spent in that lab, we discovered that seasonal hypoxic zones occurring in the Gulf of Mexico due to nitrogen-containing fertilizer runoff had major impacts on fish present within those zones. Compared to historical fish from the 1950s and 1960s and fish collected from sites that had normal oxygen levels, we found that fish collected from sites with low oxygen levels displayed evidence of ovarian masculinization – male germ cells within the ovaries. We were the first to report this phenomenon in two species of fish: spot (L. xanthurus) and bigeye searobin (P longispinosus). More than the obvious impacts this information had on Louisiana’s commercial fishing industry, this experience was the first time I saw how research could address a real-world problem. Ultimately, I realized that a career without scientific research would leave me feeling unfulfilled.

The Path to Liver Disease Research

Q: What came next in your scientific journey?

Since research seemed like it would be part of my career at this point, I wanted to join a lab that was more directly related to my undergraduate major, neuroscience. I had read a lot about hypoxia and found it extremely interesting, so I joined a lab at LSU Health Sciences Center New Orleans that had a project focused on ischemic stroke. During my time there, I gained exposure to the pathophysiology of multiple diseases through various projects, both within the lab and through collaborations. Although I joined because of the ischemic stroke project, I also contributed to projects focused on cell death in Alzheimer’s disease and through a collaboration with another group, acetaminophen-induced liver injury. My experience at LSU and involvement in these two projects helped me realize that I did not just want to make new discoveries; I want to use those discoveries to develop solutions to human disease. With that in mind, I applied to MD/PhD programs during my senior year of college.

When I got to Einstein, I continued to explore cell death mechanisms and even gained exposure to in silico drug design via rotations in the labs of Drs. Richard Kitsis and Evripidis Gavathiotis, respectively. However, my early exposure to liver biology at LSU had remained on my mind throughout these rotations, so I chose to rotate with Drs. Esperanza Arias and Ana Maria Cuervo, who had developed a collaborative project focused on autophagy failure in chronic liver disease. Almost immediately, my interest in the liver was reaffirmed, and I chose to pursue my thesis research in their labs.

Q: Tell us about your current research and your recent poster win.

My research focuses on chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) in the context of steatotic, or fatty, liver disease. CMA is very important for cellular quality control, and it allows us to regulate the levels specific proteins involved in critical cellular processes via their degradation in the lysosome. As we age, this system fails, and I'm exploring the impacts of this breakdown on fatty liver disease severity. Working under Drs. Arias and Cuervo, I use both mouse models and molecular approaches.

We have used these approaches to show that CMA activity is altered in a disease stage-specific manner, that CMA failure results in worsened disease severity, and that selective activation of CMA can ameliorate histopathologic hallmarks of disease. We were extremely excited that our poster won in this year’s retreat. To me, it reflects the enthusiasm for our results and their implications for patients affected by steatotic liver disease and other age-related diseases.

Q: What drew you to liver disease as a clinical focus?

My grandfather died of liver disease when I was less than two years old. I didn’t have the chance to grow up with him in my life, but I was told lots of stories about him and his life and as a result, knew the liver was an important organ before I even understood what an organ was.

In addition to this personal connection to the disease I now study, during my last year of undergrad, I began to discover that the many physiological roles of the liver are truly amazing. Of course, its most popular role is in detoxification, but the complexity of liver biology is quite underappreciated in my opinion. From its critical roles in maintaining systemic metabolic homeostasis to regenerating after injury, the liver is an extremely interesting organ whose malfunction results in a wide range of pathologies that cause significant negative impacts on patient quality of life.

Q: What kind of physician-scientist do you hope to become?

It’s my hope to become a hepatologist and run an academic lab focused on developing new therapies for liver disease. I want to be able to directly translate what I'm learning in the lab to real clinical problems, and vice versa. For that reason, I'm especially interested in early-stage drug development and clinical trials.

Mentorship & Community

Q: How did growing up in Louisiana influenced your outlook?

In the small town I grew up in, community means everything; people help each other without hesitation, especially after hurricanes. That deep-rooted sense of connection and resilience shaped how I think about collaboration, mentorship, and equity in medicine.

Q: How have your research mentors shaped your path?

The mentors that I have been lucky enough to have at each stage in my training have been essential to my success. Taking on an undergraduate student with little to no experience and limited knowledge of the field probably seems risky to any PI, but I was fortunate enough to find two PIs who were willing to take a chance on me. I will be forever grateful for those opportunities, because without them, I am almost certain that I would not be where I am today. In addition to the wonderful PIs that I’ve been able to work with, I’ve also consistently been surrounded by amazing people who have shaped and refined my path along the way.

Here at Einstein and Montefiore, Esperanza and Ana Maria have been incredible. They are consistently as invested in the success of my project as I am and have provided an exceptional level of support and guidance to me throughout my thesis work. From 12AM practice talks before conferences to experimental plans and advice (often in greater detail than even I can remember), they have always been there for me.

Q: How do you pay that mentorship forward?

I think success takes a village. Science is all about being on a team, and for the team to win, collaboration and lifting each other up are essential. I try to create that kind of environment and pass on what I’ve learned whenever I can.

Someday, I hope to be able to provide others with the mentorship to achieve their scientific and career goals by running my own laboratory. In the meantime, I try to pay it forward through teaching. In undergrad, I TA’d for a molecular biology course, and at Einstein, I’m a TA for the medical school’s anatomy course. I hope to build teaching into my future career as a physician-scientist as well.

Looking Forward

Q: What's next for you?

I hope to defend my thesis and publish my work by late summer next year. After this, I’ll return to the clinic to complete the final two years of medical school.

Q: The eight-year MSTP program is challenging. When the going gets tough, how do you recharge?

I love to reconnect and recharge by being outside. I’ve recently started fishing again, although I’ve learned that fly fishing is quite different from the saltwater fishing I’m used to in Louisiana. I also like to go hiking on the weekends and ski during the winter to take a break from lab and recharge. I’ve also played piano since first grade and enjoy playing in my apartment to relax.