News Release

The Hunt for Ebolavirus Hosts Narrows

January 15, 2025 (BRONX, NY)

Bats are widely recognized as the primary hosts of filoviruses, such as Ebola, yet the specific host species of ebolaviruses are not definitively known. In a new study, scientists at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the University of California, Davis, have developed a new tool to narrow down potential host species of filoviruses and better prioritize wildlife surveillance. The research is part of global efforts to prevent viral spillover between animals and humans.

The study, led at Einstein by Kartik Chandran, Ph.D., professor of microbiology and immunology at Einstein and published today in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, sheds light on the molecular rules that govern how filoviruses recognize their receptor and helps pinpoint unknown hosts of these viruses.

“The fundamental question is, where is the next ebolavirus outbreak going to come from?” said co-leading author Simon Anthony, D.Phil., an associate professor with the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine and co-lead author on the paper. “If we don’t know what the wildlife host is, we can’t know how, where or when that will be.”

The biggest filovirus outbreak, caused by Ebola virus, occurred in three West African countries from 2014 to 2016. It killed more than 11,000 people and infected more than 28,000. More recently, a filovirus outbreak caused by Marburg virus began last September in Rwanda, resulting in at least 15 deaths and 66 cases.

Unlocking the cell

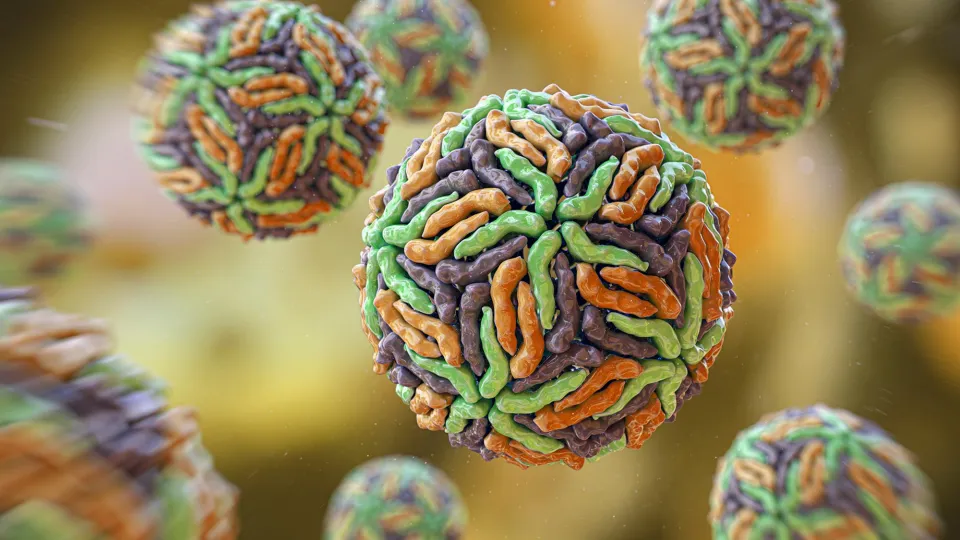

The study is the most comprehensive investigation of filovirus receptor binding in bats to date. To enter a human cell, an ebolavirus glycoprotein has to attach — or bind — to a cell receptor.

In 2011, Dr. Chandran helped discover that cholesterol-trafficking protein Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) is the critical Ebola entry receptor.

“Remarkably, all filoviruses isolated to date require NPC1 as a receptor,” said Dr. Chandran, who also holds the Gertrude and David Feinson Chair in Medicine and is the Harold and Muriel Block Faculty Scholar in Virology.

For this study, the authors conducted large-scale binding assays to evaluate how well the glycoprotein from different filoviruses interact with bat NPC1 proteins. They also used machine learning to decipher the genetic code underpinning receptor binding for these viruses.

The researchers then focused on bat species with NPC1 proteins that bind strongly to the Ebola virus glycoprotein and that live in regions where previous Ebola outbreaks have occurred. This helps narrow down which bat species have a high potential to host the virus.

“To me, this is putting together two beautiful pieces of the puzzle that are seemingly unrelated — geographic information and molecular data — all to solve the question of, will these bats be able to host the virus or not?” said co-leading author Gorka Lasso, Ph.D., research assistant professor in microbiology and immunology at Einstein.

Guiding future surveillance

This work can guide future surveillance efforts to identify the host reservoir of Ebola virus and other related viruses. As new ebolaviruses and variants are discovered, scientists can also use this method to assess their potential for infecting humans.

“Hopefully this will light the path forward, not just for filoviruses but for other viruses, as well,” said Dr. Lasso.

The research was inspired in part by a 2015 study by Dr. Chandran revealing that African straw-colored fruit bats were seemingly resistant to Ebola virus infection. The reason: Ebola virus binds poorly to straw-colored fruit bats’ NPC1 receptor.

“That really struck me,” said Dr. Anthony, who helped discover the sixth known ebolavirus strain, Bombali virus. “It became clear that there are some species that cannot be the host because they cannot be infected. Having information about which species are and are not more likely to be the host reservoir is information we should have.”

This study was funded through U.S. Agency for International Development, National Institutes of Health, and National Science Foundation’s Predictive Intelligence for Pandemic Prevention.